The Voice of the Marginalized

Salwa Bakr prefers to allow her characters to speak for themselves. She is interested first and foremost in women on the fringes of Egyptian society, outcasts, the mentally ill or the disabled, in women who have committed crimes as a result of their unfavourable living conditions and escape into fantasy or madness as a way of coping with their fate.

"I write about women who are rarely seen by others," she says. "My characters are women who remain unobtrusive and for whom no one has any use."

This represents a conscious attempt by Bakr to demarcate her work from a male brand of literature that through its patriarchal lens perceives women first and foremost as wives or lovers. "I write about widows or rejected women who are lonely, but who nevertheless have desires," says Bakr.

The view from below

Her best-known novel, The Golden Chariot (first English edition published in 1995 by Garnet Publishing Ltd.), which is a classic of Arabic women's literature, is a perfect example of this approach. With plenty of humour and elements of satirical style, the novel relates the fortunes of a handful of women who meet at the women's prison in Alexandria where they experience female solidarity of a kind they have never known before.

The book is about their desires and yearnings, which have barely played a role in Egyptian society to date. For the author, the contradiction between women's needs and the conservative expectations of women made by Egyptian society is a significant motor driving the creativity of female artists.

This view from below also defines Salwa Bakr's opinion of the current situation in her homeland. For her, the toppling of Mubarak in early 2011 was a ground-breaking experience. "My life has changed fundamentally since the revolution," she says. She saw how, through their participation in the protest movement, women were suddenly daring to do things they had previously only dreamed of. The vision of a society where men and women might enjoy equality suddenly felt attainable.

"Suddenly, women and their talents were important. They began to change themselves and gain a new perspective on themselves. They were suddenly able to make an important contribution, both for themselves and for society as a whole. For me, that was the most important message of the revolution," says Bakr.

Breaking the silence

For this reason, she cannot share the view that the situation of women has worsened since then. "It may initially seem like that, but it's not the case. Women are doing more today to fight for their rights, and that means their situation has improved," says Bakr.

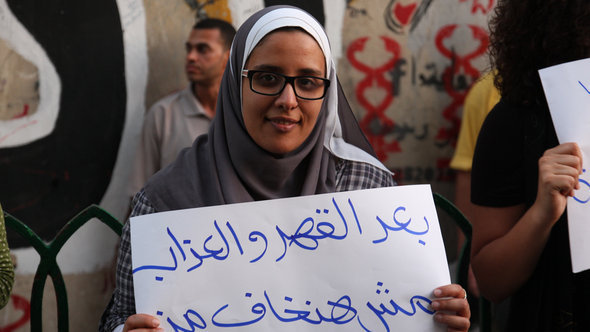

Before the revolution, no one talked about issues such as sexual harassment or rape. It was commonplace to assign blame to the victim herself, and young women in particular remained silent out of fear and shame. Now they are beginning to overcome their feelings of guilt and are also bringing cases to court concerning rape by relatives of members of the military. Courageous women are telling it like it is: "'We won't allow ourselves to be intimated anymore, after all we are not guilty, you are.' That's an enormous change," says Bakr.

Salwa Bakr was born in 1949 in Cairo, and herself comes from a humble background. Her father worked on the railways, and she initially studied Business Management then Theatre Studies at the Ain Shams University in Cairo. Following her studies, she worked as a film and theatre critic, before starting to write in the mid-1980s.

A different standpoint from the Egyptian feminist view

She had to fund the publication of her first book, but that soon changed following its enthusiastic reception by the critics. She spent a short time in prison when Mubarak was in power. Although her main focus is the situation of women in Egypt, she distances herself from Egyptian feminists and the newly-formed "Egyptian Feminist Union", for example. Salwa Bakr perceives this group first and foremost as a group of wealthy upper-class women whose mentality and lifestyles are a world away from that of the majority of Egyptian women.

She does not agree with the feminists' and liberals' lament that it is primarily the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists who are to blame for the difficulties faced by Egyptian women. "Women are not only suffering as a result of Islamist policies; they are suffering as a result of all policies that do not address their grievances," she says.

The author sees all sections of Egyptian society as being permeated by a deep-seated misogyny, which also impacts upon the discourse of liberal parties. "Egyptian intellectuals talk about politics and culture, but women's rights play no part in their debates. Essentially, their attitude to women is the same as that of the Muslim Brotherhood," claims Bakr.

This assessment is due not least to her own experience of Cairo's cultural scene. While she enjoys international success as a writer, her work lacks recognition at home – and it is evident that she feels bitter about the inner workings of Egypt's cultural sector.

She has already won numerous international accolades for her novels, short stories and narratives; in Germany, for example, the Deutsche Welle Prize for Literature in 1993. Yet she has not received a single award in Egypt. Not only does she earn less than her male counterparts, she also believes that literary prizes are not always awarded in accordance with objective criteria.

"Here in Egypt, literary prizes are awarded to male artists who also enjoy good relations with the government. If I publish a book however, I earn very little. In my view, this is also a kind of corruption," she says, clearly disgusted.

Judge the Islamists on their performance

Despite distancing herself from the feminists, she agrees with many liberals in the creative sector who say that the Muslim Brotherhood could represent a serious problem for Egypt. The triggers for the 2011 protest movement have not been addressed by a long shot: the huge economic gulf between rich and poor, the lack of perspectives for young people and the middle-class slide into poverty.

One will judge the Islamists on their performance, says Bakr. If they do not secure any progress for most of the population, then Mohammed Mursi's government will have to brace itself for massive protest.

If women's rights are restricted, Egyptian women will find the necessary mechanisms to fight back, just like the women in her novels, who do not allow themselves to be downtrodden and doggedly guard their own dignity. She has on a number of occasions seen with her own eyes female shop owners fighting back against Salafists who tried to tell them that a woman's place is in the home. The women were not prepared to listen to the views of these religious zealots and threw them out on the spot.

Bakr is convinced that that is exactly what will happen to the Muslim Brotherhood if their aim is to turn Egypt into an Islamist project. For Salwa Bakr, one thing is clear: representatives of political Islam cannot destroy the dream of a genuine civil society; the most they can do is delay its creation.

Claudia Mende

© Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de