The Estrangement of Two Allies

Against the backdrop of the major conflicts of the MENA region, the United States and Saudi Arabia are for the first time on opposing sides. Barack Obama criticised the putsch against the Egyptian President Muhammad Morsi, while Saudi Arabia welcomed the toppling of the Muslim Brotherhood leader. In addition Saudi Arabia, which perceives itself as a leading power in the Sunni world, has been following US rapprochement with arch-enemy Iran – the leading power of Shiite Muslims – with suspicion.

But the greatest anger in Saudi Arabia was triggered by Obama's refusal to bombard Syria after the poison gas attack of 21 August. The most visible sign of this was ultimately Riyadh's refusal to take up its two-year non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council. The official reason for this, cited by the Saudi Foreign Ministry, was to register protest at the inefficiency of the world body. But in reality this was a slap in the face for the US, a partner Saudi Arabia no longer believes it can trust. The Saudi royal family is increasingly breaking away from the US President.

The US-Saudi oil pact

Two historic photographs document just how close relations once were for more than half a century between what has long been the world's largest oil exporter and world's largest oil consumer.

On one of the pictures, dated 14 February 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Saudi King Abdalaziz Bin Saud sit on the deck of the American warship USS Quincy, which was in the Red Sea at the time. In return for access to Saudi oil, Roosevelt assured the King that the US would protect the territorial integrity of the Kingdom and from then on, treat it as America's most important partner in the Middle East.

The Saudi King needed a robust ally, and the United States also needed a reliable partner. During the Cold War, Saudi Arabia would remain the most important partner in the Arab world. Egypt, Syria and Iraq fell into the orbit of the Soviet Union, and Iran, the second pillar on the Gulf, fell away with the 1979 Revolution.

Fear of US-Iran rapprochement

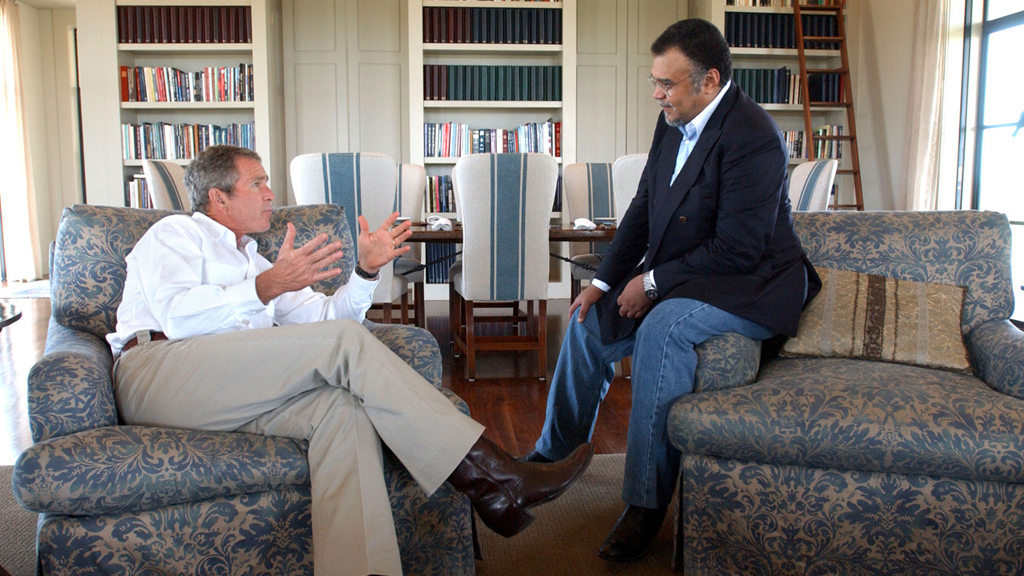

The second historic photo, dated 27 August 2002, shows US President George W. Bush on his farm in Crawford chatting with the similarly casually dressed Saudi Ambassador Bandar Bin Sultan Al Saud, who is shown sitting nonchalantly on the arm of a sofa. Contact between the two was so close that even on 9/11 when airspace had been closed down, Bandar managed to secure permission from the President to fly Saudi citizens back home in two aircraft.

The fact that 15 of the 19 attackers were Saudi citizens inflicted initial long-term damage on these relations. Earlier resilience tests, such as Saudi criticism of US support for the foundation of the state of Israel in 1948, were short-lived. At the time, Saudi Arabia did not consider itself to be threatened by the new state, neither from a foreign policy nor a domestic policy point of view. It was more important to the Saudi King to safeguard American support, both political and military. Not least in view of the burgeoning Communist threat and the approaching surge of leftwing Arab nationalism.

Unprecedented alienation

Three developments over recent years have led to an unprecedented alienation. Firstly, the Saudis feared the upheaval that took hold in parts of the Arab world in 2011.

The Saudis openly criticised the United States for allowing both Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Zain al Abidin Ben Ali in Tunisia – both long-term allies of Washington and Riyadh – to be ousted. Washington condemned the putsch in Egypt on 3 July 2013, while Riyadh played a role in this. The Saudis fear that the ideology of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood could find some appeal among their (young) population and endanger the rule of the dynasty of Al Saud.

While the Saudis' Salafist system of order stipulates that the country's rule is subject to that of the leading clan, to Al Saud, thereby allowing Wahhabi theologians to shape society, the Muslim Brotherhood calls on every citizen to get involved in politics. To prevent such ideas from spilling over into their nation, the royal family plans to buy loyalty with an unprecedented expansion of what is an already generous welfare state. But this will only buy them time; popular satisfaction is not lasting. The national budget already requires an oil price of more than 80 dollars per barrel of crude oil. And public dissatisfaction continues to grow, as shown by recent demonstrations by women against their driving ban.

Secondly, the Saudis fear an American conciliation with Iran. In the event of a successful rapprochement, all Arab Gulf states would lose their preferential treatment by the Americans, and they would no longer be of importance to Washington on the Gulf. This is why the Gulf states are blowing the same horn as Israel and warning the West against "cowardice" in dealings with Iran. The greatest Arab fear is a Shiite axis secured by the Iranian bomb.

For this reason, the Saudis and other Gulf states are trying to oust the Bashar al Assad regime in Syria at any price. Since Saladin in the 12th century, the Sunni Muslims have pushed the Shiites back and onto the sidelines. Now, for the first time, a counter movement has arisen – with a Shiite axis from Tehran via Baghdad and Damascus to Beirut. The Shiites will defend this axis; with the toppling of Assad the Sunnis see an opportunity to break it. The refusal of Obama to bombard Syria, as well as his rapprochement with Iran, are destroying this hope.

Row over Washington's energy policy

Thirdly, America's energy policy shift is threatening Saudi interests. When the US attains energy independence it will no longer allow itself to be blackmailed by oil producers in the Gulf.

When the US economy no longer uses oil from the Middle East, the US government will no longer be willing to invest in the region's security architecture. This would leave the Gulf states looking for new security partners.

The foreign policy goals that Saudi Arabia – even in contradiction to those of the United States – is prepared to pursue, are becoming apparent in Syria. Here, the Saudis are not supporting the rebels that Washington would prefer to see as victors, but the only Salafist militia and jihadists that Riyadh believes can topple Assad. It was only recently that Bandar Bin Sultan, who is now head of the intelligence agency, began trying to weaken those jihadists with an international agenda – or in other words an agenda that extends beyond Syria.

A second front in the Saudi engagement in the Syrian civil war is the battle against Shiite Iran and its Shiite-Alawite ally Assad. With its massive support for the Sunni rebels, the Saudis have played a significant role in the confessionalisation of the conflict. In addition, on a third front they must prevent the Muslim Brotherhood from becoming too strong in political opposition. This is why, for the post of Chairman of the Syrian National Coalition, the Saudis succeeded in installing a sheikh from the Shammar clan – that of the mother of the Saudi King Abdallah.

To date, the Saudi royal family has managed to keep destabilising developments in the region at a safe distance from their own subjects. But nevertheless, the golden days of the wealthy Gulf states are numbered. It would be an illusion to assume that they will remain unaffected by the turmoil.

Rainer Hermann

© Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung / Qantara.de 2013

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor Lewis Gropp / Qantara.de