Erdogan's youth, religious but not educated?

The Turkish public has been debating the shortcomings of the education system for weeks. The discussion was triggered by a report published a few weeks ago by the Ministry of National Education: the ABIDE study – roughly comparable to PISA elsewhere – evaluates the performance of Turkish pupils. The result: many Turkish pupils have devastating performance deficits. Above all, their performance in mathematics and Turkish leaves much to be desired.

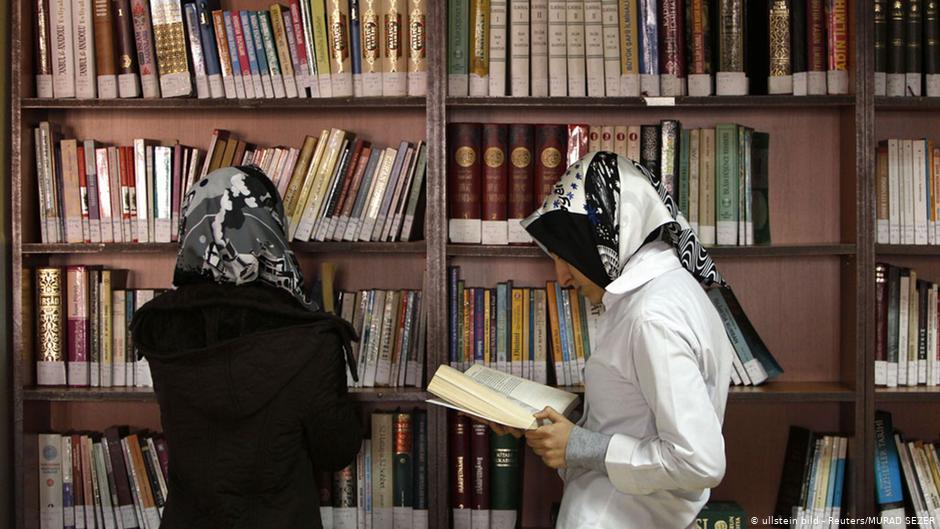

Many opposition members and experts blame the so-called Imam Hatip schools for the educational misery. These are schools that focus on religious subjects – the Koran and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad are given high priority in the curricula. Originally such schools were used to train imams, but reforms introduced by the Islamic-conservative AKP government in recent years have aimed at making the schools more socially acceptable.

Hundreds of new religious schools

As a result more and more such religious schools have begun emerging: according to the Ministry of National Education, the number of middle schools has tripled in the last five years from 1099 to 3286. The number of Imam Hatip secondary schools also rose sharply: from 537 to 1605 – there are now more than 620,000 such high school students in Turkey. To facilitate such a quantity of new religious foundations, some state schools were simply converted overnight – in many cases without the consent of either parents or pupils.

Perihan Ozgun is one of many mothers who demonstrated against this sudden restructuring. She is particularly outraged by the fact that her child's Istanbul school "60th Yil – Sarigazi" is discriminating against non-religious pupils. While half of the institution remained an ordinary secondary school, the other half was converted into a religious school. The classes are smaller and cleaner in the religious part and the fees are lower, she complains.

Religion at the expense of education?

Critics see a connection between the poor performance of Turkish students and the many new Imam Hatip schools being founded. It is often pointed out that Imam Hatip schools are particularly poor at the Turkish Central Examination – something Turkish students have to pass to gain access to higher education.

Data from the Ministry of National Education confirms the charge: only 38 percent of Imam Hatip school leavers matriculated in 2018 after passing the central examination, which is a rather poor figure compared to other schools.

The Turkish government admits there is need for improvement. The Ministry of Education launched the "Natural and Social Sciences Project" in 2016. "The aim is to improve the chances of success of Imam Hatip graduates in the central examination, but also to integrate more social and natural science subjects into the curricula," explains Ozgenur Korlu of the Education Reform Initiative (ERG).

Ozgenur, however, remains sceptical that these measures will bring the desired success when it comes to central examination results. "The Anatolian ("Anadolu Lisesi") and natural science secondary schools are still top of the rankings."

Ali Aydin, general secretary of the Free Education Union, is disturbed by the fact that the discussion focusses too much on religious schools. "Rather than talking about the shortcomings of Imam Hatip schools, we should be addressing the structural problems of our entire education system," says Aydin.

Erdogan wants a "religious generation"

As a child, Turkish President Erdogan himself attended an Istanbul Imam Hatip school in the 1960s. At that time, schools like his former primary school were a rarity. But since he came to power, he has made religious schools mainstream – a matter close to his heart.

In the past, he has often stressed that he would like to see a "religious generation" growing up. By intervening in the youth and education system, he is trying to anchor conservative Islamic values in the younger generation. It can therefore be assumed that the religiousness of Turkish pupils is at least as important to him as their secular education.

Burcu Karakas and Daniel Derya Bellut

© Deutsche Welle / Qantara.de 2019