Whiz kid from the ghetto

It is the most successful debut in the history of Danish literature. Since its publication in autumn 2013, a collection of poems by Yahya Hassan has sold 100,000 copies in Denmark. In a country with just over five million inhabitants, where poetry is usually printed in an initial edition of 400 copies and selling 3,000 copies makes a novel a bestseller, this is simply incredible.

What's even more unusual is that the author, Yahya Hassan, is just 18 years old and grew up as the son of Palestinian refugees in the port town of Aarhus – or more precisely in the new district of Gellerup, which has a reputation for being a rough neighbourhood rather than the cradle of poetical genius.

The satellite town on the outskirts of Denmark's second-largest city is a classic immigrant ghetto; most of Gellerup's residents arrived there from Palestine, Turkey, Somalia or Iraq, and the district is plagued by poverty, unemployment and crime.

"We didn't have a plan"

In younger years, Yahya Hassan smoked marijuana and stole, was up in court for committing petty offences and spent much of his youth in reform institutions and homes before becoming an literary star overnight. It is unclear when and how he began to write. A teacher with whom he had an affair apparently supported him in his efforts. He alludes to this fact in his poem "Contact Person". The woman in question has in the meantime published a novel in Denmark about their relationship.

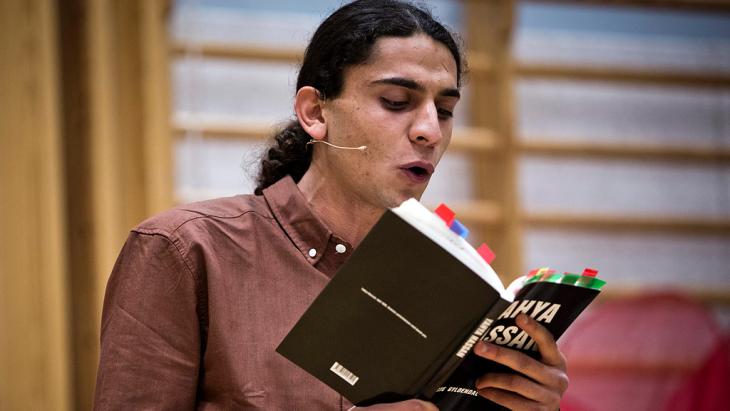

But when the young writer presented the German-language edition of his poems at the Leipzig Book Fair in the spring, wearing sunglasses and a sports jacket, his hair pulled back neatly into a long ponytail, he stressed in interviews that he had taken part in rap workshops and written his first texts at the age of 13. However, he soon found the genre too superficial and cliché-ridden and turned instead to poetry.

Set in capital letters, Hassan's poems, usually short and concise like Japanese haikus, and sometimes drenched in grim, dark humour, tell of religious bigotry, petty crime and fatalism in the immigrant ghetto.

There's the father who is outwardly pious but beats his children, the mother who ducks away from him, and the young "Gellerup wogs", as he calls them, who deal in drugs and stolen goods and despise the Danish welfare state.

Sometimes Hassan mimics the immigrants' slang, writing in broken Danish or using the drastic vernacular of the street, full of expletives and obscenities. His poems have titles like "Burglary", Slayer" and "The Seventh Home", or sometimes "Festival of Sacrifice" or "Ghetto Guide".

"My aunt believes in relatives / but her husband believes in the casino/ And the other men believe in cash in hand," reads a terse line about his family. Some sentences might also serve as aphorisms: "We didn't have a plan, because Allah had plans for us."

Dense language

Yahya Hassan has the ability to condense small stories or episodes into a few verses. His poems are strongly autobiographical, evincing much of the intensity of spoken-word poetry. When he recites them, they have the force of angry rap volleys and the despair of a fevered prayer. His melodic, rhythmic presentation style reminds some reviewers of a muezzin.

Particularly haunting are the passages telling of his father and his parenting principles.

"He didn't say habibi / he said hands or feet / and broke a slat out of the wooden frame," he writes in "Wooden Slats". Rarely has the cold logic of domestic violence been so vividly encapsulated. And yet the son's feelings remain ambivalent: "Maybe I would have loved you / If I had been your father and not your son," the author reasons in his poem "Father Unborn Son", and elsewhere he speaks of wishing that the man who gave him life might be "more than just a refugee with full beard and jogging suit", as other Danes see him.

Voices from the margins of society

The rage and enormous power of this angry outcry are reminiscent of Kanak Sprak, Feridun Zaimoglu's 1995 debut, in which he lent a voice to the unemployed, the pimps, the rappers and the Islamists, alienating their words into a pidgin German. He subtitled his book "24 Misstöne vom Rande der Gesellschaft" (24 Broken Sounds from the Margins of Society).

Hassan's description of the abysmal depths of family life also recalls "Das Scheißleben meines Vaters, das Scheißleben meiner Mutter und meine eigene Scheißjugend" (My Father's Shitty Life, My Mother's Shitty Life and My Own Shitty Youth), the book in which the journalist and writer Andreas Altmann recounts a youth full of abuse, humiliation and bigotry in small-town Germany, in the Bavarian pilgrimage town of Altötting during the post-war period.

Yahya Hassan himself cites as influences the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the autobiographical epic series of novels by the Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgard and the Danish poet Michael Srunge, who committed suicide in 1986 – all of them writers who devoted themselves to the dark side of the human psyche.

Co-opted by political groups?

Hassan's success has not sprung from the indisputable literary quality of his debut collection alone. It can only be understood by being viewed against the backdrop of the immigration debate, which has been fought out more vehemently in Denmark in recent years than almost anywhere else in Europe.

For ten years, from 2001 to 2011, the right-wing populist "Danish People's Party", which agitates against immigrants and Muslims and portrays them as a threat to the national culture, has supported a conservative minority government, thus managing to push through one of the most restrictive sets of immigration laws in Europe.

Tensions escalated in 2005 with the controversy over the Mohammed cartoons. Like Hassan, one of the men behind the cartoons, Kurt Westergaard, who narrowly escaped an attack in 2010, comes from Aarhus, which is why the almost hysterical adulation being showered on the young Danish-Palestinian author in his homeland leaves a questionable aftertaste.

Although Yahya Hassan wants to be regarded first and foremost as a poet and not to be politically co-opted, his book provides the members of Denmark's frightened educated classes with authentic ghetto horror stories and might even have the effect of confirming some of them in their prejudices: yes, that's just what they're like, those Muslim migrants.

The publisher is actually fostering this misunderstanding by celebrating Yahya Hassan as a taboo-breaker. His first big interview in "Politiken" – Denmark's leading left-wing liberal daily newspaper – caused a major stir, constituting a frontal assault on the first generation of immigrants.

"Those of us who dropped out of school and became criminals and bums were not let down by the system, but by our parents," Hassan said, thereby taking a load off the shoulders of all those Danes plagued by a guilty conscience and doubting the justness of their system. However, it is often overlooked that many of his poems can also be read as an indictment of Denmark's institutions, its reform homes and social workers.

Unpopular statements

Hassan views with contempt the excuses some migrants make for their own failures, and he rejects radical Islamists and radical right-wingers alike. He calls them "two variations of extremists who take society hostage", and he is certainly right about that. In television and newspaper interviews, however, he has let himself be carried away into making generalised statements about Danish Muslims, catering to the prejudice that all immigrants are lazy and violent and are only out to rip off the state.

This has made him into a target of hatred in some circles. Since being attacked last year at Copenhagen's central railway station and receiving multiple death threats, he is now accompanied by bodyguards wherever he goes.

Despite this protection, he was attacked in Ramallah by unknown assailants in early June 2014 while visiting the West Bank for a reading, and at the opening of the new central mosque in Copenhagen just a few weeks later he was booed at and denied admission. A local politician from Aarhus, Mohamed Suleban, brought charges against him on the grounds that his generalisations about districts like Gellerup are racist.

Nevertheless, none of these circumstances should distract attention from the fact that Yahya Hassan is a great talent, nor should they cause people to read too much into what the young author sometimes says in interviews. He is only 18 after all, and his poems speak for themselves.

Daniel Bax

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de