A Metaphor for Heavenly Paradise

For many Western tourists visiting the Islamic Orient, the region's bazaars, mosques and palaces are the main attraction. Archaeological sites (which are the expression of advanced ancient civilisations, some of which existed for millennia), the many different craftsmen's skills that have been handed down through the generations to the modern day, as well as several other examples of an uninterrupted ethnic culture and its traditions in both urban and rural settings round off this 'view from the outside', which is often superficial and very simplified.

However, despite all the enthusiasm for the impressive remnants of what were predominantly urban civilisations and their regional and historical diversity, rarely a thought is spared for the circumstances under which they were created and the principles on which they were based. Of all the various factors involved, water is undoubtedly the most important. Apart from the countries of the great Nile, Euphrates, Tigris and Indus river basins, most of the Islamic Orient is dominated by deserts and steppes. Drought and water shortage are the most striking ecological characteristics of this region: water is the element that dominates all life.

The density of vegetation, the variety of animal life and human activity – especially agriculture and urban developments – would all be inconceivable without an adequate supply of water. In the midst of an extremely arid landscape, oases of different sizes are the crystallisation points for rural and urban civilisations.

These oases take the form of extensive areas of irrigation agriculture on the outskirts of cities, of carefully planned gardens surrounded by high walls in residences belonging to rulers or religious communities, of carefully contained and intensively cultivated fruit groves in the middle of desert-like surroundings, or of modest house gardens and green areas with small basins of water in the middle in the inner courtyards of urban residential buildings. They are oases of agricultural production, oases of peace and contemplation, and oases of relaxation. Water and vegetation that provides shade are essential features of every one of these islands.

The gardens of Islam: the Koranic perspective

Given the often extreme living conditions in the arid areas of the Islamic Orient, it comes as no surprise that oases and irrigated gardens have a very special status in the Muslim religion, the statements of the Prophet, and the holy scriptures. In this context, Sura 13, verse 35 of the Koran plays a very special role that is cited again and again. It reads:

'The parable of the Garden which the righteous are promised! – beneath it flow rivers: perpetual is the enjoyment thereof and the shade therein: such is the End of the Righteous ...' [translation by Abdullah Yusuf Ali]

Other parts of the Koran also contain powerful descriptions of the appearance of the paradise that awaits the faithful, what it contains, and the delights it holds in store. Sura 76 not only promises springs that burst forth from the earth (verses 5 and 6), but also shady groves, trees, and bushes, whose fruits are within easy reach and are just waiting to be enjoyed (verse 14). Abundance and happiness in the hereafter are the wages that are worth striving for by leading a holy life here on Earth.

Faced with such promises, it is not surprising that the region's ornamental gardens and, in particular, the gardens belonging to rulers from Morocco in the West to the Mughal Empire in the East are often described as earthly paradises, a metaphor for the heavenly paradise and an auspicious precursor of a future life after death.

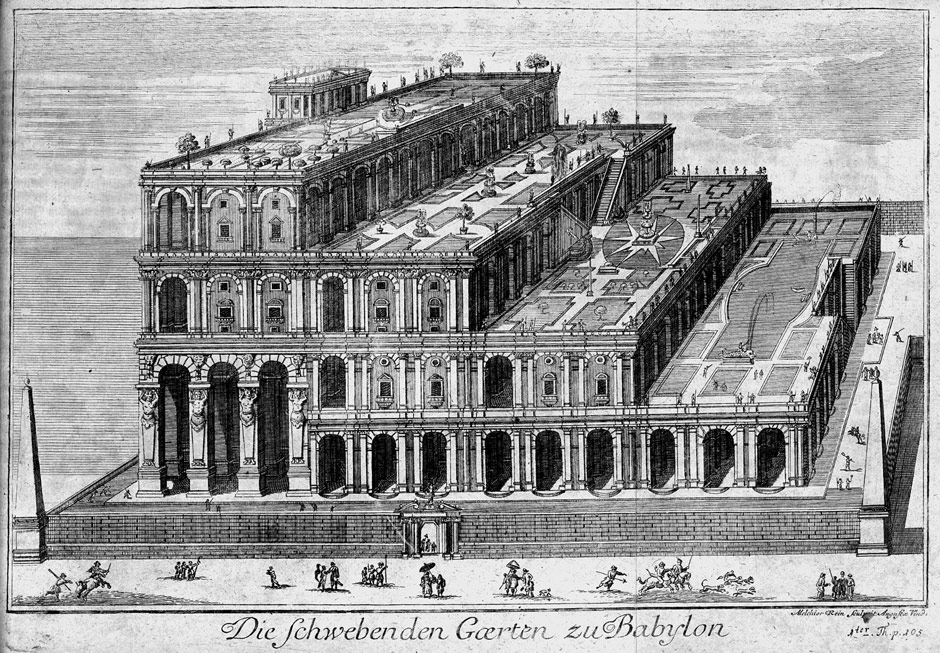

However, no objective study and assessment of the garden culture of the Islamic Orient, which is a major part of the material and spiritual culture of this region, would be complete without a reference to the pre-Islamic roots of this phenomenon. Not only Semiramis' legendary Hanging Gardens in Babylonian Baghdad, but also the magnificent gardens of the Achaemenids in Pasargadae in Persia and the other sovereign's residences dating from the fourth and fifth centuries BC anticipate all the elements of what would later become Islamic garden culture.

The same can be said for the influences of the Occidental Antiquity. The Greeks and above all the Romans lived their urban lives in villas with water features and lush gardens, or in country houses outside the gates of the cities.

Quite apart from the fact that such residences still exist in modern-day Italy (villas, villeggiatura, palazzi), the Romans established and lived this way of life, which is now over 2,000 years old, in their provinces, which stretched to the banks of the Euphrates.

Naturally, the gardens of the Islamic world really only acquired their spiritual aspect – and consequently their unique combination of religion, spirituality, and culture – when they were made a metaphor for and used as the image of Paradise. In a detailed commentary for a Berlin exhibition on the subject of the 'Gardens of Islam', the journalist Camilla Blechen described the role and significance of these earthly paradises as follows:

'The Prophet Mohammed, the mouthpiece of Allah, mentions this heavenly place around 130 times, a place whose channels are replete with water, wine, milk, and honey, where the shade of high trees promises relief from the searing heat, and seas of flowers fill the air with beguiling scents. As the place where the blessed reside, this Garden of Eden, which is planted with roses and narcissi, date palms and pomegranate trees, promises those who have been swept away to the hereafter after leading a holy life on Earth sublime pleasures of all kinds. This inventory of Paradise, which was easily comprehended by the human mind, helped stabilise the structure of the Muslim faith, which now has 1.2 billion followers worldwide.' (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 21 January 1994, p. 35)

The gardens of Islam: a typology of earthly realities

But what form do the earthly realities of these examples of Islamic garden culture, which are so impressive in terms of both art history and culture, actually take?

This begs the question as to whether one starts with what can only be described as a typically 'Western' typology of Islamic gardens (e.g. the garden graves, palace gardens, and pleasure gardens Moynihan describes in her book Paradise as a Garden in Persia and Moghul India, London 1980) or whether one differentiates between gardens in different civilisational areas (as does Attilio Petruccioli, one of the best experts on Islamic urban and landscape design). Petruccioli highlights the differences between the Arab, Persian, and Turkish 'concepts of nature, landscape, and, consequently, space' and their correspondingly different interpretations of the Koranic paradise and its earthly representations (A. Petruccioli, publisher, Der Islamische Garten, Stuttgart 1995). Whichever way one looks at it, water and dense vegetation that supply shade and coolness – preferably combined with fruit-bearing trees and bushes – are always fixed features of these earthly paradises.

Regardless of their function, location, and size, almost all Islamic gardens adhere to more or less the same design criteria. Both their basic framework and structure-giving central axis are watercourses in the form of artfully designed pools, channels, and basins bordered by flowerbeds and promenades that invite visitors to take a stroll. On either side of these promenades are mirror-imaged pairs of planted areas (lawns, flowerbeds, trees, and shrubs) arranged in geometric patterns.

One widespread garden design is the so-called 'Chahar Bagh' (four gardens) pattern. This basic pattern – which can be modified and reproduced within the garden as often as required, depending on its size and topographical situation – can be found across the entire area where Islamic garden culture is found. Particularly charming are those instances where gardens are arranged in terraces and where flights of steps and water cascades connect the various different levels. Pavilions too, baldachins made of marble, galleries set into watercourses, and seating were all intended for the paradisiacal well-being of the people who used the gardens. Fountains of all kinds or small artificial waterfalls also decorated the building complexes along the central axes and at their ends, thereby contributing to the intimacy of these oases in the middle of their harsh surroundings.

The golden age of these earthly representations of heavenly circumstances lasted from the early advanced Arab Islamic civilisations of the eleventh/twelfth centuries – especially on the periphery of the Maghreb and in Andalusia – to the period of Mughal rule on the Indian subcontinent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It goes without saying that these gardens were created over both a vast area and a long period of time, which resulted in different styles and formal patterns of garden architecture and garden culture. Generally speaking, however, one would not be wrong in thinking that over the years the originally contemplative religious character of the gardens increasingly gave way to a more secular need felt by rulers to demonstrate their status.

Increasingly, the gardens of Islam became gardens of the Islamic world, i.e. creations of art and art-historical significance that were commissioned by rulers and dynasties who were not only appreciative of art, but also hungry to demonstrate their status. As such, they were the equivalent of the European gardens of French absolutism or the English landscape gardens of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Gardens in the Islamic world: places of relaxation and the 'green lungs' of cities

Today's gardens in the Islamic world have developed into earthly paradises of a very different kind. On the one hand, they are both of art-historical significance and technically impressive in terms of the water technology they feature. They have become destinations for national and international tourists and are now commercial enterprises. One of the most beautiful and most famous examples of all are the gardens and water features of the Alhambra in Granada, with its artful combinations of buildings with filigree decorations, orange groves, flowerbeds, and water features of all kinds.

However, the gardens of the Moroccan royal cities of Fez, Meknes, and/or Marrakesh are also evidence not only of religious spirituality, but also – perhaps even more so – of the artful symbiosis of architecture, water management, and garden design. The Persian gardens, most of which were destined to be not so much places of religious contemplation as places of retreat for rulers, are also famous: the Fin Garden (Bagh-e-Fin) in Kashan, the gardens of the Safavid rulers in Isfahan, or the Eram Garden (Bagh-e-Eram) in Shiraz are just a few of these.

Finally, the pinnacle of Islamic garden culture is represented by the magnificent Mughal creations, from Kabul and Lahore to Delhi and the Shalimar gardens in Srinagar, Kashmir. The gardens of the Mughal emperors in particular, and the fact that they were created on the shores of Lake Dal in the temperate uplands of Kashmir, show that the ultimate aim here was to ensure the earthly wellbeing of the imperial potentates and their entourage – to the detriment of the Mughal subjects, who had to pay crippling taxes and work their fingers to the bone. This short list of gardens, which makes no claims to being exhaustive, is one side of Islamic ornamental gardens in the Orient, which now uplift secular visitors and inspire amazement.

Another side is the increasing use of gardens previously used either for religious purposes or by rulers as areas that are open to the public, that can be accessed by city-dwellers and are urban recreation areas. One impressive example of this is the famous Chahar Bagh (four gardens!) Boulevard in the centre of Isfahan in Iran. This boulevard was once part of the Safavid palace precinct and its gardens. Today it is one of the central axes of the city, which has over a million inhabitants. Although it still features channels of water and trees that provide shade, it is now lined on one side by businesses, hotels, and restaurants.

The same applies to many of the magnificent gardens in the Maghreb. Central Asia is a special case. Here, centuries-old palaces, mosques, and gardens dating from the Samani, Timurid, and subsequent eras in Bukhara, Samarkand and elsewhere, were considered examples of religious feudal insignia of power during the Soviet era and were turned into public parks and opened to the public at an early stage. Generally speaking, one can say that almost all earthly paradises were once situated on the outskirts of cities or far beyond their city walls. However, rapid urban growth in the countries of the Islamic Orient has seen many of these gardens being swallowed up by the cities, turning them into 'intra-urban' green areas. This means that they have become welcome, hugely popular public recreation areas for today's stress-ridden city-dwellers.

So while the gardens of Islam have a centuries-old tradition of being a symbiosis of spirituality, art, culture and nature, in today's thoroughly rationalised world they now have an additional function to which hardly any attention has yet been paid, namely that of being the 'green lungs' of sprawling urban areas. Modernisation, motorisation and industrialisation have turned many cities into thermal incubators with smog and a short supply of fresh air. This is particularly true of the Islamic Orient, which has always been a hot and dry area.

Green areas, water reservoirs, and trees with large crowns of foliage provide cool respite and clean the air. Evaporation is the process that lowers temperatures and creates refreshing coolness. In this way, these once-exclusive earthly paradises acquire a relevance in modern-day urban areas that was not originally intended by the people who provided the money for their construction. They can safely be referred to as playing a fundamental part in the modern 'green city' debate and the role of green spaces for the urban climate.

Today, however, it is not only the carefully-planned parks and gardens of the past that influence city climates. Cultivable land used for agriculture in urban areas, and even the many small inner courtyards in residential buildings, which often have nothing more than bathtub-sized basins and a meagre sprinkling of decorative plants, create microclimates that make many city-dwellers feel that their immediate environment is heaven on Earth. Courtyard houses, where the rooms are arranged around a central inner courtyard, can be found throughout the entire Orient. These houses are predestined to be this kind of oasis, with a microclimate of relative coolness.

Depending on the social status of their residents, these houses may be magnificent building complexes with considerable water reservoirs surrounded by shady trees and porches. The houses are either the residences of city merchants and traders or of big landowners who prefer life in the city to life in the country. Nevertheless, most houses fall into the first category, and have modest house and courtyard dimensions. In these cases, the water basins are tiny and are often surrounded by just a few pot plants. The inner courtyards are often so small that they are covered in water-soaked sheets of cloth in the summer months to increase the cooling effect.

The effect of water and vegetation, which influences the local microclimate, also applies to the countryside and its villages. Enclosed gardens and fruit groves are not only used for agricultural production, but also as oases of peace, cooling freshness, and human relaxation in a rural setting for villagers and for city-dwellers in search of peace and relaxation who live near such oases.

Gardens in Islam – earthly paradises: for the devout Muslim, the promise of the life hereafter; for rulers, a display of their status and a place of relaxed pleasure; for modern-day city-dwellers and country-dwellers alike, oases of peace and relaxation from the stresses of daily life! It would not be wrong to say that religious reflection and meditation hardly play a part now in these gardens, which are no less magnificent than they were in the past. Instead, commerce and consumption have taken over the use of these earthly paradises. Above all, local, regional, and international leisure play the biggest role. It is only in the very recent past that the significance of these historical gardens for urban climates has been acknowledged. Culture and Nature are entering into a new symbiosis.

Eckart Ehlers

© Fikrun wa Fann / Goethe Institute 2013

Qantara.de editor: Lewis Gropp

Eckart Ehlers is Professor Emeritus for Geology at the University of Bonn.

Translated by Aingeal Flanagan

Qantara.de editor: Lewis Gropp