Reincarnating ancient heroes

Indonesians are currently crazy about the ″Mahabharata″ series screening on AnTV. This comes not long after viewers enjoyed the ″Mahadeva″, the prelude to the ″Mahabharata″. Many reasons explain the popularity of this Indian wayang, from the glamour of the actors, who look almost like Indian film stars, to the ″royal″ setting of the series, which has captured viewers′ dreams with its lustre. There is also the intellectual aspect: Indonesian viewers appear engrossed in what we might call the ″philosophy″ of the series.

Another reason behind the craze might be the fact that the Mahabharata is not at all foreign for Indonesian television viewers. Even those who know next to nothing about wayang nevertheless know the five pandawa. No one would disagree with that, but if this is true, can the same be said of the Indonesian comics that have dealt with the Mahabharata?

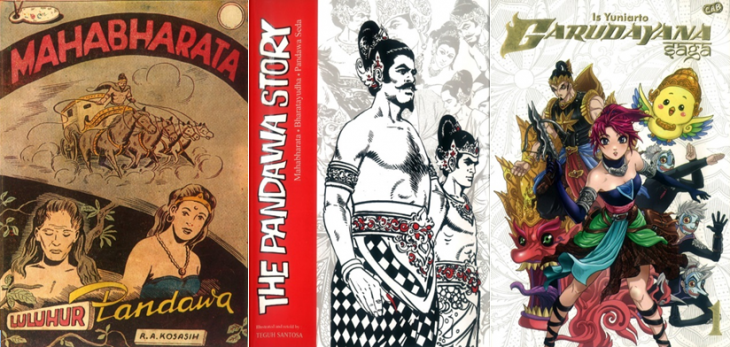

In the 1950s R.A. Kosasih (1919–2012) experienced great success with Indonesian audiences while also being loyal to the episodes of the Indian epic. He played a significant role in enriching the world of wayang with references to the land of its origin, which he adapted from M. Saleh′s version of the Mahabharata published by Balai Pustaka in 1949.

This was noticeably different from the more recent ″Mahabharata″ created by Teguh Santosa (1942–2000). Along with its sequel, ″Bharatayudha″, it revealed little of the cultural realities of our own environment. In 2009, this work was re-launched for limited circulation.

A reincarnation

The 2009 editions still took the form of the eight-page episodes which Teguh had made for the children′s magazine ″Ananda″ in 1984. The process leading to these new editions was a major undertaking.

First came the documentary and archival processes. By 2009, the episodes had been spread in all directions, so it took years to collect and trace back all the episodes of the epic. This detective work was not done by a researcher or professional archivist, but by lovers of Indonesian comics who saw the importance of preserving the work and bringing it back to life. They did not feel this way about all comics, but only about the ″suitable and proper″ ones that fitted their ideology about the nature of comics.

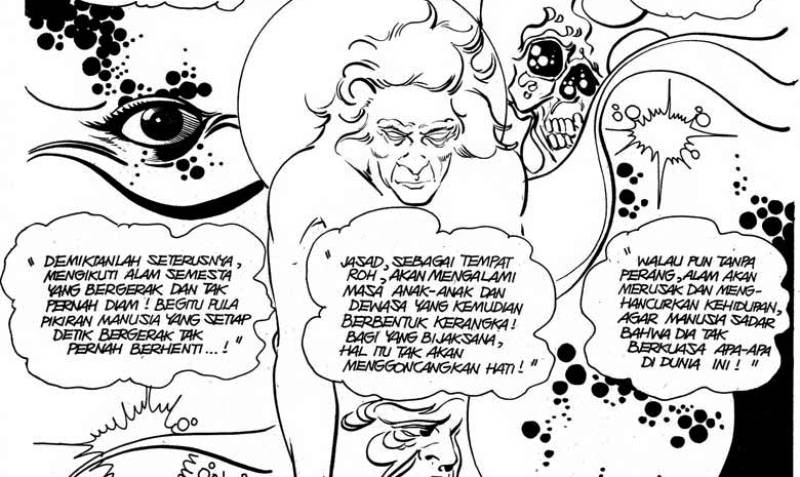

The second phase concerned the artistic dimension, which required assistance from contemporary technology. The withered and dusty pages from ″Ananda″ were scanned, not in a random and casual way, but with the intention of preserving the work as well as reproducing it. The process made the comic shine by maintaining and also ″remastering″ it, but in an ethical way that preserved Teguh Santosa′s creativity. The printing used paper that would not diminish the quality of the drawing, which was comparable with that found in the Marvel Comics. In fact, the American comics publisher had once recruited Teguh.

The binding and cover design are significant from an artistic perspective, for they give us insight into a negotiation that had to be made with the dominant discourse of the world of Indonesian comics. The cover did not feature illustrations by Teguh Santosa, instead carrying images by contemporary illustrators such as Apriyadi Kusbiantoro and Admira Wijaya.

Reminiscent of modern-day gym instructors

In these new interpretations, we do not find representations of warrior nobles (ksatria) representing spiritual or mental harmony according to the classical conception of wayang kulit. Instead, the figures on the cover are attractive only for their bodily forms. As a result, the warrior nobles of the wayang have bodies like those of gym instructors.

This new interpretation was considered intelligible to the dominant readership of today. With their bulging biceps and intimidating faces, the figures resemble the superheroes of contemporary epics found in comics anywhere, and in films and video games.

Third, although the transformation of the comic′s packaging into something amazing was an expression of respect and appreciation for the work, the final production ended up being printed on demand only, showing the reverse image of the hegemony dominating the contemporary Indonesian comic market. This is clearly not a translated manga comic printed on newspaper, printed and circulated en masse to satisfy a monthly readership, and in the process becoming a cheaply-priced, mass-produced commodity.

But the developments of the last 25 years cannot be undone. Indonesia′s comic lovers can only accept and give their blessing to them.

Opposition

We are not currently witnessing a ″war″ in which Indonesian comics fight, guerilla-style, against the domination of Japanese comics. In my view, Japanese comics have already become part of the Indonesian comic world. The serial ″Garudayana Saga″ (2013/2014) by Is Yuniarto is proof of this. This could be called a manga-style wayang comic.

Yet the reincarnations of the creations of the old comic artists who gained mythical status in the past introduce an oppositional cultural discourse. In all aspects, they provide negative reflections of the manga comics (which, it needs to be pointed out, are also distributed by actors in the Indonesian comic industry).

From the archival perspective, the Indonesian reincarnations are conveyed and circulated in ways that compete with the intellectual property written into the international manga contracts; in their presentation, their expensive production values compete with an economy geared to mass-production; in their marketing, the guerilla-style business practices of specialised communities compete with the big publishing networks that form parts of conglomerates with universal distribution.

In 2013 Teguh Santosa′s comic versions of the ″Mahabharata″ and ″Bharatayudha″ were printed as one with the title ″The Pandawa Story″. In this edition, the cover featured Teguh′s work. These Indian texts have been ″Javanised″ since the eleventh century, but this edition brings them into a new domain of struggle. The same can be said of the comic versions of the Mahabharata, which give evidence of cultural struggles distinctive to processes of Indonesian cultural change.

Seno Gumira Ajidarma

© Inside Indonesia 2015

Prize-winning journalist and novelist Seno Gumira Ajidarma lives in Jakarta. His 2012 book ″Panji Tengkorak″ (Gramedia) is an analysis of the comic of the same name by the artist Hans Jaladara.