Being a stranger in a second language

When you leave your home or familiar environment – either voluntarily or by force, through migration or displacement – you are likely to feel alien in your new environment. People migrate for different reasons and feel alienated in different ways, by the physical space – the location itself – or by the new language that now surrounds them.

While the experience of alienation is highly individual, and can occur not only abroad, but in one’s own home country or even family, the pain and trauma of a disaster, man-made or natural, exacerbates this experience.

It goes without saying that we are all the products of the specific place and culture we were born into thanks to the processes of enculturation and socialisation. This is the world we get used to live in, where we feel secure, safe, and confident, because we know it and it knows us. We have a sense of belonging to this world.

The opposite is true for places we don’t know, which instil insecurity and fear in us. This division between familiarity and unfamiliarity, between home and foreign place, shapes our minds, thoughts and lifestyle. Because humans are domestic beings, creatures of habit, they draw a line between familiar and unfamiliar world. Therefore, when something feels strange and alien, they will attempt to familiarise and adapt until they can consider it a home.

“Language is the home of being”

As a matter of fact, we were all born into a specific culture, society, family, place, and language. It is through our native language that culture, beliefs, ideas and countless other things were and are conveyed to us, and it is how we communicate them to others. We live in that language and grow with it; it shapes our ideas and our life as a whole.

Our native language relates to our being, to our very existence. Therefore, it has a certain ontological dimension. As Heidegger wrote, "language is the home of being". But could we not say that this statement is especially true of our native tongue.

The second language cannot be the home of our being in the same way as our mother tongue. This ontological dimension merely exists in our native language. Because we were born in it, have lived with it, and grown up with it, our whole life is formed by it. If "knowledge is power", as Francis Bacon once said, then we were armed with knowledge in our native language, and we are most powerful in our native language.

I was born to a Kurdish family. As Kurds, we don’t have our own independent state, and Iraqi, Iranian, Turkish or Syrian IDs are imposed on us. We are refugees in our homeland. With the exception of Iraq, where Kurdish became an official language after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, Kurdish is neither official nor allowed to be spoken in the countries we currently inhabit. We have no choice but to learn a foreign language. As a result, we become alienated in these second languages.

Anfal-isation

My first confrontation with a second language was with Arabic, because, in Iraq, we had to learn Arabic. My father had been "anfalised" in the 1988 Anfal campaign (al-Anfal, Eng. the spoils), a genocide committed by the Ba’ath regime against the Kurds to solve the "Kurdish question" in Iraq once and for all. I never met him, as I was only three months old when he was " anfalised".When I heard the word anfal for the first time, it sounded awkward and strange to me. I did not understand the word because it was an Arabic-Islamic word from the Koran. But I realised that it was related to my father’s absence and death. For me, anfal then became a synonym for fatherlessness.

I heard the word anfal again at school in Islamic education. In these lessons, we had to memorise Koranic verses, which taught us the words’ forms, but not their content. The word anfal still haunts me today. It affects the way I perceive the Arabic language, and contributes to my feeling of alienation in this language.

My experience with the English language is entirely different, because I have been learning it voluntarily with the clear aim in mind of studying in an English-speaking country. When I went to England to do my master’s degree in philosophy, everything was new to me.

It felt like my familiar world was destroyed, turned upside down overnight. First of all, I was confronted with radical changes in terms of culture, beliefs, my own self, and my very existence in language. I felt estranged in the English language because, in the beginning, I could not speak well and express myself properly. I had to familiarise myself first with this new linguistic world.

A reflection of the new world

In my third language English, I felt estranged and alienated as it was a reflection and expression of the new world that surrounded me, where everything looked and felt different from my old one. My old self was at stake and my new one had not arrived yet. I had to rebuild myself from scratch at the expense of my old self, casting it aside and, at the same time, I had to track my new self down.My new self was in its infancy; now I was a work in progress. Within me, my native language and old self stood in confrontation with my third language and new self. On the one hand, I embarked upon an exciting journey of finding my new self through my third language; nothing ventured, nothing gained. On the other hand, my old self was clinging to me in my native tongue. I was hanging over the abyss between them.

When you are in a totally new world like this, and have left your old one behind, you are physically in that place, your body is there, but your mind has not yet arrived. You still live and dwell in your own native language, you still think in your own language. This is because your memories and your past are rooted in your native language. When you want to communicate with your new world, you must do it mostly through its language.

Limited language skills mean limited power

But this can be a tricky process, as you will initially feel the need to formulate your thoughts in your mother tongue in your head, which you then have to utter as a translation. If you cannot express your feelings, your ideas or, indeed, yourself easily in the new language, problems inevitably present themselves. Thus, you feel alienated, and sense that your identity and personality are at stake. You feel weak and vulnerable because the weapon of language is not yet at your disposal to defend yourself. Limited language skills mean limited power.

After what can seem like forever in confrontation with the new language, it finally happens and you learn it. All the time you have invested in language classes and awkward conversations with native speakers finally pays off. Therefore, learning another language has an epistemological dimension.

You might be learning a second or a third language, but it never replaces the native one, which is natural and ontological. You can say something, and express yourself in your mother tongue, but you will never achieve that to the same extent in another language. For instance, you may have memorised some poems, you use sayings and proverbs, jokes, stories, fairy tales, and curses in your native language, but the likelihood is you will never be able to replicate exactly this in the second language.

Native language as a constant

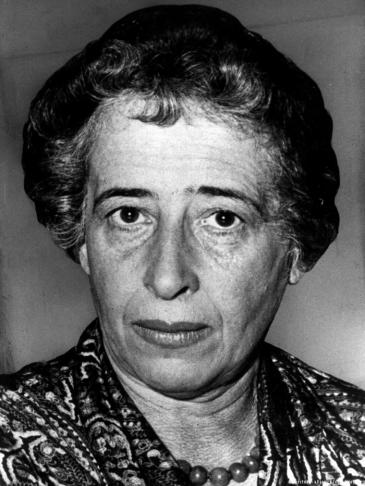

Hannah Arendt, in an interview with German journalist Gunter Gaus in September 1964, spoke about her mother tongue as a continuous element throughout her life, having fled from National Socialist Germany to France, to the USA, and having returned to Germany after the war:

"What has stayed with me? The language. […] And I have always consciously refused to lose my mother tongue. I have always maintained a certain distance to both French, which I spoke well at the time, and English, the language I write in today. […] You see, there is a tremendous difference between your mother tongue and all other languages. In my case, it is very easy to explain. In German, I know a great number of German poems by heart. […] This can, of course, never be achieved again."

Speaking a second language will never quite be the same as speaking your mother tongue. However, this does not mean it is not worth the effort to master it. After all, you might discover a new self in the process.

Nabaz Samad Ahmed

© Goethe-Institut/Perspectives 2018

Nabaz Samad Ahmed, was born in Koya, Kurdistan, in 1988. He has an MA in Ethics and Political Philosophy from the University of Manchester, England and an BA in Philosophy from Koya University, Iraq. Currently, Nabaz is an assistant lecturer at the University of Sulaimani in Kurdistan. He is also a writer, translator and a member of the editorial board of “Culture Magazine”, a Kurdish cultural quarterly.