What English is missing

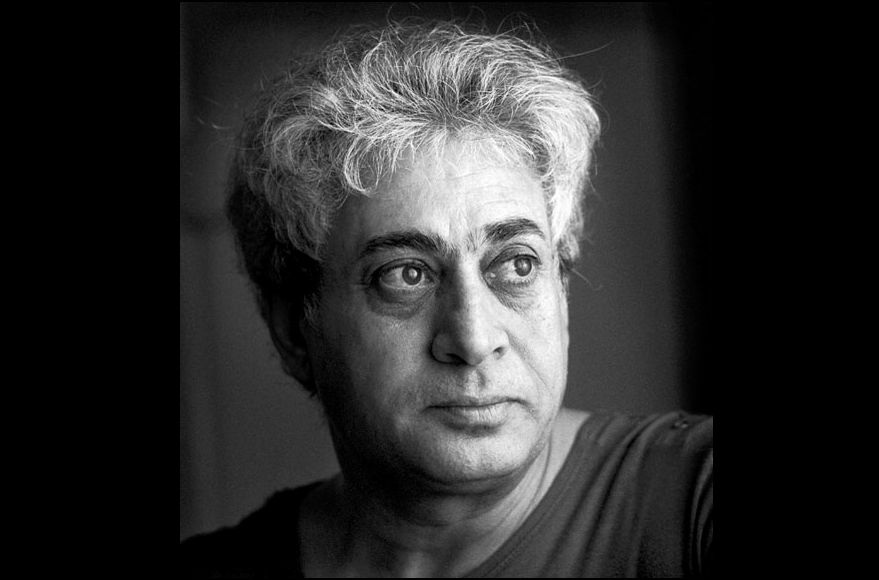

The first publication by Kurdish Syrian writer Salim Barakat (born in 1951) was a poetry collection called Each Newcomer Shall Hail Me, So Shall Each Outgoer (1973). With this book, a Kurdish youth who was just twenty-two, whose face was full of childish amazement and whose innocent look did not hide the glimmer of intelligence, gave a violent jolt to the surface of a stagnant Arabic poetry scene. Even Adonis said of Barakat: "This Kurdish boy carries the keys to the Arabic language in his pocket."

So Salim Barakat came and while still in his early twenties, he crafted a poetic language that was highly individual, a language that was overpowering, compelling and flagrantly rebellious. This language was both engineer and vehicle of a power hitherto unseen – even in Beirut, regarded during the 1970s as the capital of a new Arab modernity.

Barakat′s Kurdish themes were unfamiliar territory for the Arab reader, as they would be to the Western one. He addresses, with defiant imagination, the clash of history, geography, story and myth. Yet his poems are not without familiar elements, as their structure and vision echoes the Arabic classics. But these poems are re-formed, shaped from sentences that have a nervous tension, a strange fragmentation.

Works breathed from the soul

It′s not only poetry by "Salimo" (the name by which he′s popularly known in Kurdish) that is so distinguished; his novels too take a similar approach and yet stretch the imagination still further. His fiction is epic, although not in the traditional sense. Here, we find ourselves confronted with language that has the rhythmic sound and flow of the classics, but also avoids the banal, or any compromise in favour of the normal or ordinary.

Barakat′s language demonstrates how a poet can master an extraordinary eloquence, engage with a wide range of vocabulary and formulae and yet look and sound as though the works were breathed from his soul, given life from the heart of dictionaries both abandoned and re-imagined.

To talk about Salim Barakat is to talk about this departure from the ordinary. He stands alone among other Arabic modernist writers. Even the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, Barakat′s close friend, asked: "What are the sources of your language? What are the sources of your imagination?" In Darwish′s poem " The Kurd Has Nothing But the Wind," the last poem in the collection Don′t Apologise for What You′ve Done, he writes of Salim Barakat.

Barakat not only seems to reside within the Arabic language, but, under his hand, the language becomes new: it holds the land, the mother, desires. The heat of this upheaval sweeps through what Barakat has written in different forms. Thus a man, from his early twenties to his sixty-fifth year, has threaded through his pages the senses in conflict, as well as the battles of stones, plants, animals, passions and planetary orbits.

His forty-six works are divided into twenty-one collections of poetry, a memoir of childhood and another from boyhood, a book of essays, a textbook and twenty-two novels. Barakat′s style is unique not only to Arabic literature, but to contemporary world literature of the last fifty years.

Arabic – his only homeland

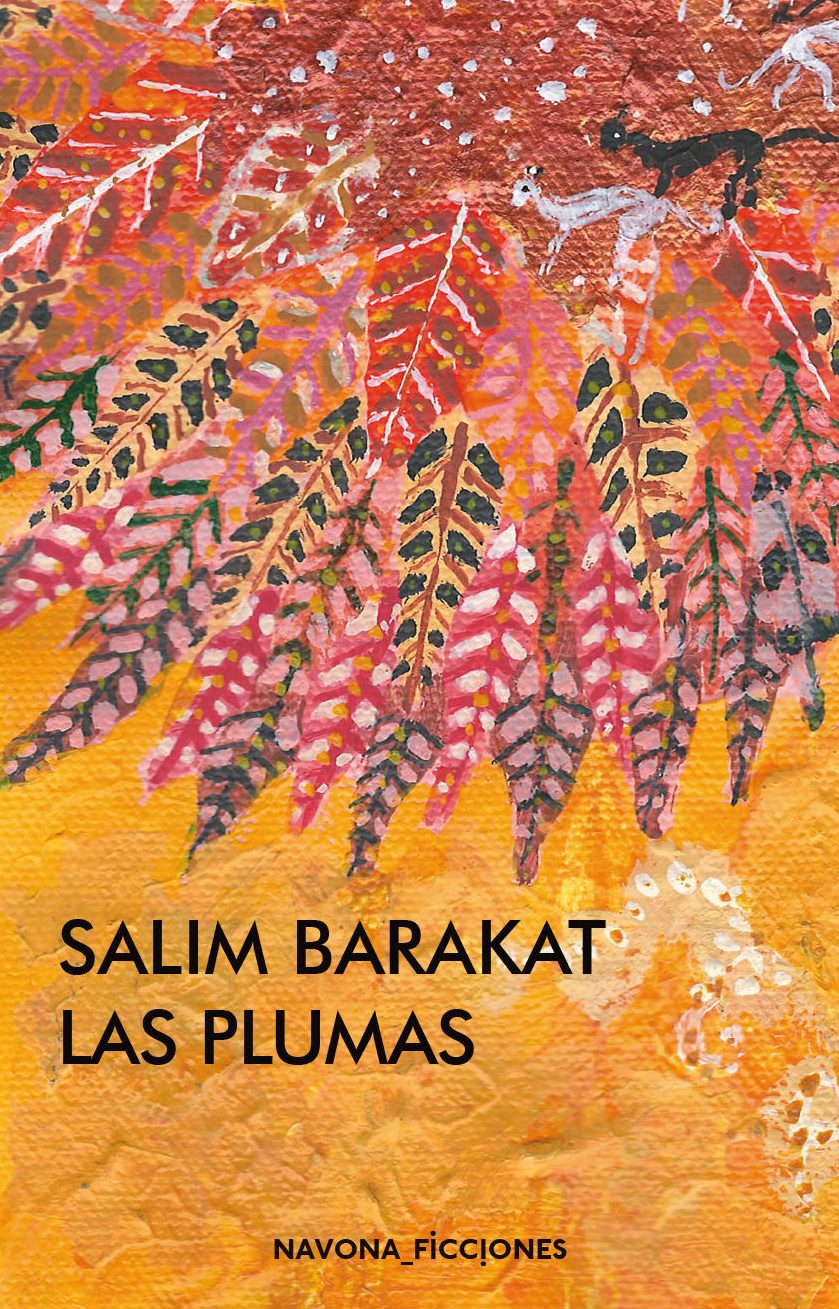

Barakat was born in Qamishli, in northern Syria and passed through Damascus, Beirut and Nicosia on his way to Stockholm, Sweden. Through all this, the Arabic language has been Salim Barakat′s permanent homeland, which he has carried with him everywhere he lived. This was the only part of his homeland that did not abandon him. I remember when the novel Les Plumes (The Feathers) was translated into Spanish. The introduction was written by the great Spanish writer and translator Juan Goytisolo.

Goytisolo writes of welcoming Barakat′s literary experimentation:

"Salim Barakat′s prose, like that of a Lezama Lima, is a constant gift of inventions, inspired images, striking metaphors, unexpected turns, poetic sparks, winged flights. A prodigious mixture of reality and dream, of legend and bitter chronicle, it does not obey the laws of time, nor those of place."

An authentic feast

Goytisolo adds: "The text wanders in a kind of visionary geography, of fleeting and changing monuments: Kurdistan is a thousand times dreamed in contrast with the Cyprus lived, in childhood and adulthood, the real with the fantastic. Mem, the main character, is transformed throughout the work, once a bird and once a jackal, he converses with both humans and animals. The freest creation of Barakat transgresses the borders of plausibility."

And also: "Barakat′s richness and texture owes nothing, as some all too easily say, to Faulkner or Garcia Marquez. His writing involves layers of myths, legends, memories, chronicles of past and present tragedies, under the surface of which lies the melancholy history of the town of his birth."*

Goytisolo ends with: "Les Plumes is an authentic feast for us, this species threatened species with extinction, we lovers of reading and re-reading of all great novels."

As we remember this conversation and Barakat′s incredible literary production, we remember he is now in his sixty-fifth year, having spent nearly twenty years in the isolated Skogas Forest outside of Stockholm, Sweden. Yet despite this isolation, Barakat′s work has found its way into Swedish, Spanish, Catalan, French, Kurdish and Turkish.

Remember this and feel frustrated because a literary voice unique among living writers (not only in Arabic literature, but in world literature) has no complete work available in English at this moment, whether his poetry, his autobiography, or his fiction.

Remember this and remember the difficulties faced by James Joyce and Marcel Proust, by Faulkner and Marquez in publishing their work in translation.

Remember this and think how in English, the world′s most common language, readers don′t have access to the literary works of Salim Barakat, how this must frustrate not only those readers who are interested in Arabic literature, but all who are interested in exceptional literary experimentations in other languages and cultures.

Must we wait until Salim Barakat is awarded a Nobel Prize for English translations of his work?

Mahmoud Hosny

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated by M. Lynx Qualey

*This paragraph was translated by Andre Naffis–Sahely in a review in Banipal magazine.