"Politics is made on the street by the people"

"I have authorisation. I'm allowed to do this," says the bearded young man with the chin-length hair and impish grin as he lights a cigarette during a reading of his latest book, "Young Losers", in Berlin. The public laughs. He's pleased. He's sitting there in a hoodie with a black leather jacket on top – the trademark apparel of the rebellious young author.

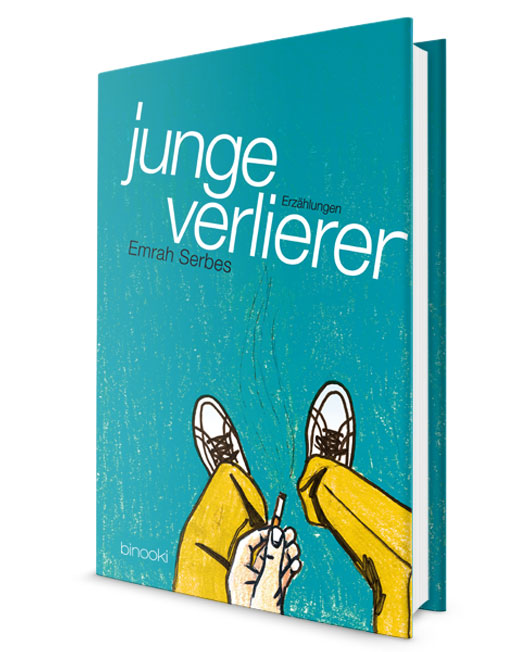

"Young Losers", which has just been published in German translation, is a collection of short stories written from the point of view of young people. It deals with issues related to growing up. There's the young boy who, after the death of his parents, is sent to live with his grandmother, who needs her daily dose of medicine to survive. Or the 14-year-old who's hopelessly in love with his older brother's girlfriend. Or 12-year-old Nurettin, who wants to avenge his soldier brother's death. The protagonists are all young men who in one way or another have suffered a loss, and who express their frustration and grief in desperate acts.

Popular critic

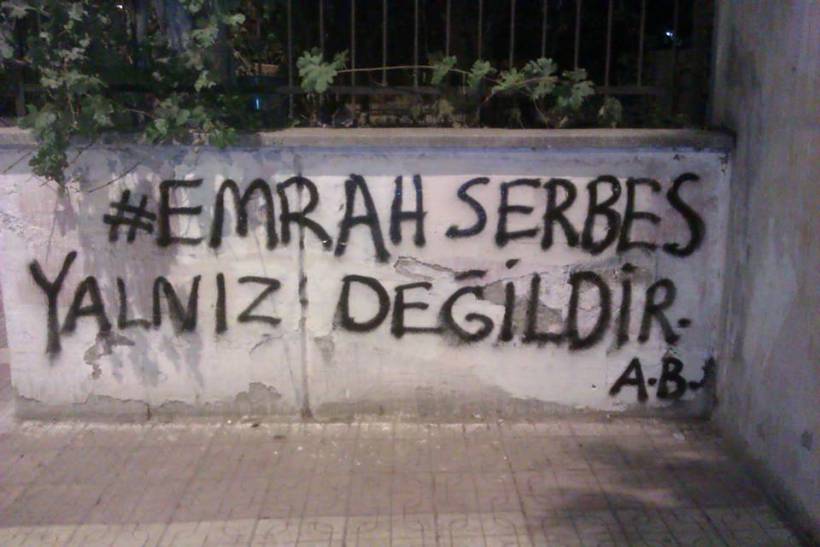

In "Young Losers", Serbes gives a voice to young people whose problems are often neglected in the adult world. It's only since the Gezi movement in the summer of 2013 that Serbes himself has been regarded as the voice of the people. At the time, he not only participated in the street demonstrations; he also repeatedly appeared as a guest on non-mainstream media talk shows, where he made no secret of his criticism of the violent tactics used by the police and the AKP government. As a result, the Istanbul prosecutor's office demanded he be sentenced to twelve years imprisonment: the charge, however, was soon dropped.

Serbes was not intimidated. "This government has long since lost all legitimacy," he says. "If it's only a question of money for you, then just take all the money out of the state budget, but clear off once and for all!" His comments are directed towards all the AKP politicians – including Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan – who have been accused of privately enriching themselves through bribery and corruption, after a number of recorded telephone conversations found their way into the public domain.

Serbes was not in the least surprised when discontent with the government exploded in the Gezi movement. "So much has been pent up in this society for years," he says. To him, the situation is quite clear-cut: "When you constantly chase a man who earns around 400 euros a month with a broom, you shouldn't be surprised if one day he turns around and comes at you with a shovel."

According to Serbes, the events of the summer of 2013 set something in motion that is still far from resolved. "Elections by themselves do not decide politics," he comments. "The real protagonists in politics are the people, and the place where politics is conducted is the street. This is what Hannah Arendt said, and we in Turkey have finally learned this lesson. The fact that Gezi Park still exists is not the result of a decision made by parliament or the courts. It's the people who decided." Serbes only hopes that the situation does not continue to escalate.

Literary sensation

Writing is something that Serbes has always done. His father was a labourer and his mother a civil servant. They both wanted their son to take up a profession that would allow him to earn a proper living, so he tried working in the hotel sector in Antalya until it became clear that this wasn't his thing. He decided to stake everything on one card, and the gamble paid off. His first novel about Behzat Ç., a cantankerous, chain-smoking, foul-mouthed, alcoholic police commissioner with the homicide division in Ankara, took the Turkish literary scene by storm. Serbes uses both subtlety and irony to inject criticism of the police force into the plot, which focuses on the protagonist – a prototypical anti-hero – and other authentically-drawn characters. The novel served as the basis for one of the most popular TV series in Turkey, which was constantly censored by the television and radio supervisory authority. It's even been dubbed into German, and a film version was released in 2013.

"I don't deliberate about what to write. I don't search for themes. It's more the case that the themes find me," says Serbes, describing his creative process. Sometimes, he says, young people ask him how to write when they haven't experienced all that much in life themselves. "I think you don't necessarily have to experience something in order to write. Life and writing are two different things," he answers. He doesn't regard himself as an "intellectual writer". Of course he enjoys reading good novels but, above all, he's a keen observer. He adheres to the view of Mario Vargas Llosa, who said that you have to believe in writing as in a religion.

When he has to meet a deadline, he leaves the teeming metropolis of Istanbul and his home in Beşiktaş, which is constantly frequented by his friends. He returns to his native city of Yalova, where his mother still lives. He documents his productivity in a calendar that sits on his desk. On some days, he records the letter N. This means he succeeded in working on a novel. Other days he marks with the letters HN, meaning that he was half-successful in his writing. Sometimes the calendar is marked with a B. These are the days he just "bummed around." On good days, he says, he can work up to sixteen hours. "I'll write ten or twenty pages, although only one page is really usable. Sometimes it's only one sentence. Then I think, 'I have produced a usable sentence. That's all right.'"

Three of Serbes' books have already been translated into German, and he's already achieved a certain degree of notoriety in Germany. His books are on the curriculum of two Berlin secondary schools. The students express enthusiasm for his fresh tone, which also owes a great deal to the sassy translation by Oliver Kontny – "My German voice," says Serbes. He jokes: "I now find myself part of a continuum with Goethe, Hesse, Günther Grass, and Heinrich Böll. In another five years," he adds, squinting through his cigarette smoke, "I'll have left them all behind."

Ceyda Nurtsch

Translated from the German by John Bergeron

© Qantara.de 2014

Editor: Charlotte Collins/Qantara.de

Emrah Serbes was born in 1981 in Yalova. He studied theatre in Ankara. Emrah Serbes' books include "Her Temas İz Bırakır" ("Every Touch Leaves a Trace"), "Son Hafriyat" ("The Last Excavation"), and "Erken Kaybedenler" ("Young Losers"). They are published in German by Binooki-Verlag.