Who needs parents?

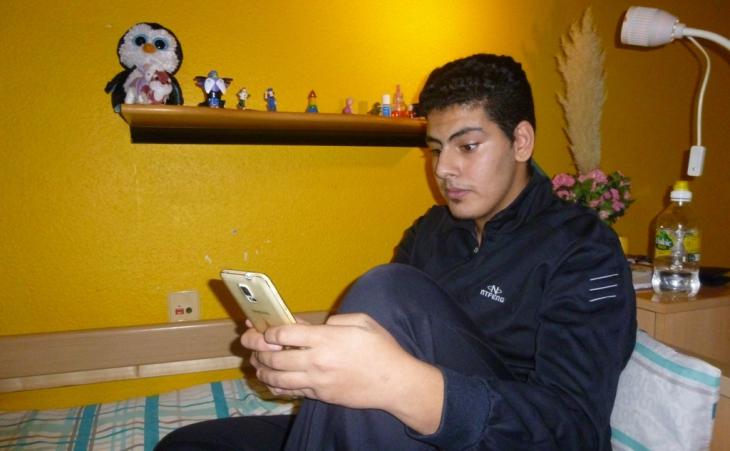

The conspicuous yellow of the walls is broken by two posters depicting beautiful desert landscapes. A cuddly toy penguin sits atop the small shelf over the bed; next to it some Nivea Creme and a copy of the constitution or Basic Law of Germany. From the place where he sleeps, Fardus looks directly out on to the church spire in a small village in Hesse close to the German town of Limburg.

For about a year now this three-bed room in refugee accommodation has been his home. In November of 2015, the then 16-year-old, along with his two older brothers, fled from Syria to Germany. Though they have now separated, the mother and father still live in Syria. Fardus's sister and her husband have been missing for months.

The next month will be a critical time for the young Syrian and his brothers, because Fardus will shortly turn 18 – for the family to be granted a legal right to stay together, his mother will have to have made it to Germany by then. "My mother is the most important person in my life. I can't do without her. I am really afraid I will never see her again," says the 17-year-old, fighting back tears.

Hardship regulations not being applied

According the German constitution and the Geneva Refugee Convention of 1951, refugees who have been officially confirmed as such in Germany, have the right to have their immediate family members join them. The immediate family is defined as including spouses and their children, but not parents. However, minors do have the right to have their parents join them. At least, that was the rule, until recently.

When Germany adopted its new "Asylum Package II", however, the right to family reunification was strongly curtailed. The new regulations suspended family reunification rights for refugees with a limited or subsidiary protection status for a period of two years. This also applies to minors and their parents.

The suspension represents a clear violation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, says, Karim Al-Wasiti from human rights organisation PRO ASYL. Meanwhile, following the conclusion of the negotiations on "Asylum Package II" in early 2016, the country's Social Democratic Party (SPD) called it a victory for "humanity". This referred to an agreement reached on a so-called hardship provision, by means of which the parents of minors with limited refugee status could be allowed to join their children immediately. According to a recent investigation by German broadcaster ARD, however, this has never actually happened.

Status restrictions on the rise

Fardus is still waiting to hear about the outcome of his asylum, application. He is hoping that, with the help of a lawyer, he may be granted the full refugee status that would enable him, legally at least, to bring his mother to Germany. This could well be a vain hope, however. Since the introduction of "Asylum Package II" the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) has been increasingly opting for giving only subsidiary protection to Syrians. This would mean that his only chance of bringing his mother over to Germany would be if he were to qualify for application of the hardship regulations – an almost hopeless prospect.

Ever more young people are now living without their parents in a country that is foreign to them. According to the human rights organisation PRO ASYL, the proportion of asylum seekers being granted only limited protection rose from less than 20 percent in spring to more than 70 percent by August of last year. "This has a devastating effect on the young people," says Karim Al-Wasiti, "they spend so much time worrying about their families that they cannot concentrate on their school work."

Chaotic bureaucracy

Fardus turns 18 later this month. Time is running out for him and he is worried. Along with the long-awaited BAMF decision on his eventual fate, there are numerous other, almost insurmountable, difficulties and bureaucratic deficiencies to be faced. "Until the end of 2015, the authorities took the view that underage refugees should not be invited to interview," says Sylvia H., a voluntary worker who looks after Fardus.

"The problem here is that one regulation cancels out the other," she says. Once the refugees come of age and an invitation to interview becomes possible, they find themselves in the position of no longer having any right to bring their parents over to join them, because they are no longer minors.

Since January 2016 the BAMF authorities have been instructed that they should also invite minors of 14 years and over to interview. In practice, however, the employees are often unaware of this, Sylvia explains. "Whenever I was at the office and tried to organise my family reunification, they would tell me that ′only when I had official refugee status would I be able to bring my mother over′," Fardus explains. "You get an invitation to an interview when you are 18. But that is the very condition you have to meet in order to be given refugee status."

Precious time was lost. Thanks to the persistent efforts of their volunteer refugee worker, Fardus and his two brothers have been able to book a visa appointment for their mother at the German consulate in Istanbul. This is nothing short of a small miracle as the waiting time for visa appointments at German consulates is currently at least a year. The shocking lack of personnel is something deplored by Karim Al-Wasiti. "We are talking here about 94 people in six German offices trying to deal with all the applications for family reunifications." It is simply not enough, he says.

Appointment or not, Turkey remains off-limits

A visa appointment is not, however, the only obstacle that must be overcome and the failure of family reunifications is often due to last-minute hitches. This could also happen in Fardus's case. His mother will have to travel from Damascus to Istanbul to keep her appointment at the German consulate. To do so, she will first of all need a Turkish visa in order to enter the country.

"Since the beginning of last year, however, there are effectively no Syrians able to enter Turkey or Jordan, even when they have an appointment at a German embassy or consulate," says Karim Al-Wasiti. PRO ASYL has already taken the matter up with the German Federal Foreign Office, in the hope of persuading them to talk to the Turkish authorities and make it possible in such cases to obtain easier access to the country. But so far the situation remains unaltered.

"At the moment, Al-Wasiti laments, there are two German authorities handling the family reunification procedures: one, the embassy in Beirut, the other in Erbil in northern Iraq." It makes for long waiting times. The German Embassy in Erbil is currently taking 15 months to process visa applications.

With each day that passes, the hopes of Fardus and his brothers of getting their mother out of Damascus and bringing her to Germany diminish. There may be one small glimmer of hope however. The German Foreign Office could arrange a special appointment at the Germany embassy in Beirut – maybe even before Fardus's 18th birthday.

Ulrike Hummel

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the German by Ron Walker