"Tunisia Needs Help!"

Mr Barroso, only three months after Tunisia's Jasmine Revolution of January 2011, your plane touched down on the runway of Tunis-Carthage International Airport.

You had come to congratulate the Tunisian people on their successful revolution for freedom and dignity. At the time, your office in Tunis released a statement that you had signed in which you described Tunisia as "leading the movement for freedom and democracy in the Arab world". In it, you went on to say that it was the European Union's "responsibility to support these historic reforms".

Since then, while you have devoted your attention to other projects that fall within your remit as the most senior representative of the world's most important alliance of states, Tunisia has been busy healing the inner wounds inflicted on it by an oppressive and corrupt regime.

The threat of a new dictatorship in a different guise

Almost three years have passed since the overthrow of the country's former president, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. We assumed that these three years would suffice to lay the foundation of a truly democratic state built on pluralism and diversity. However, what we are experiencing right now gives serious cause for concern that the country may end up under the yoke of a dictatorship in a new guise.

After all, although Tunisia has signed most of the international human rights conventions and is, therefore – at least morally, until such time as a new constitution has been drafted for the country – bound by these conventions, there is a gulf between the day-to-day reality of life in Tunisia and the country's international obligations.

The right to freedom of expression is not of limited duration; it cannot be revoked at will. Recently, however, a quick succession of prison sentences have been handed down to human rights activists, artists, independent journalists and opposition politicians for daring to express their opinions in public. In many cases, local authorities felt offended by these opinions. The same old laws and ordinances that were used by the previous, oppressive regime have been dug out, modified, and are being used once again to put people behind bars for speaking their minds.

50 years' curtailment of the freedom of expression

For 50 years, we experienced the curtailment and restriction of civil rights and liberties. We rose up against this in the firm belief that freedom of opinion, expression, and conscience are inviolable human rights.

But what we are seeing now in "post-revolution" Tunisia gives rise to the fear that alarmingly, developments seem to be taking us backwards rather than forwards.

Pompous claims that Tunisians now enjoy collective and individual civil rights and liberties – which are held to be the main achievement of the revolution of 14 January – are, to put it mildly, a complete exaggeration. It is true that everyone – without exception – can become politically active, that private and non-profit-making organisations can go about their work without surveillance or pressure, and that the same applies to the right to demonstrate and the right to free assembly. All of this is laudable. However, the real threat is now to the individual and personal freedoms of the men and women of Tunisia.

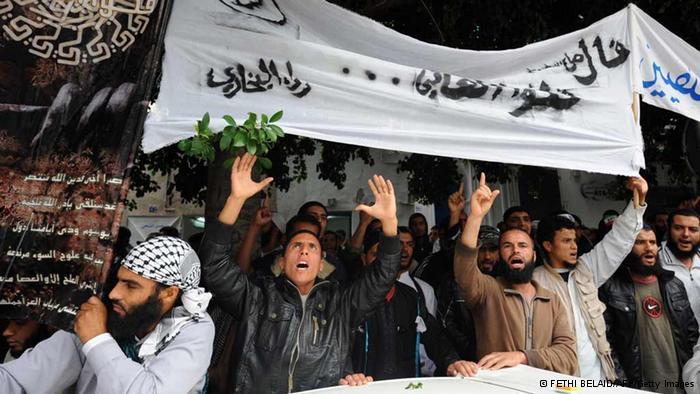

For example, extremist religious groups are exerting considerable pressure, using violence to force Tunisians to renounce their moderate attitude to life in favour of another that can legitimately be described as medieval and backward.

Religious moral guardians gaining ground

Let me give you just one example in this respect. An organisation known as the Association for the Respect of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (Al-Amr bil Maarouf wa Nahy an al-Monkar), which is working hard to instil fear and dread in Tunisians who have chosen a free and independent lifestyle. Yet the Tunisian authorities are doing nothing to stop this organisation!

Similarly, imams in some mosques, which according to the law are under the supervision of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, never tire of declaring the behaviour of large parts of Tunisian society to be un-Islamic – obviously believing that these people are living in contradiction to religious teachings.

Although this can be viewed as a form of freedom of expression, when such behaviour goes hand in hand with the tendency to use violence and to commit murder and manslaughter, the state must take steps to stop such excesses. Unfortunately, however, it rarely does.

For an independent and neutral judiciary

A state that is truly governed by the rule of law needs an independent and neutral judiciary, something that still seems to be a long way off in Tunisia. The executive bends the judiciary to its will as its sees fit by making sure that the Ministry of Justice tightly controls the Office of Public Prosecution, using it to launch manipulated proceedings against political opponents.

The freedom of the press is also subject to strict limitations and the press has to resist attempts to curtail it. Within the space of a year, Tunisian journalists have organised two general strikes to protest against physical attacks on journalists and to give voice to their rejection of the government's policy, which seeks to dominate public media organisations by using its monopoly to fill key executive positions.

As you will undoubtedly have heard, terrorist organisations are gaining ground outside the capital. Terrorism, which knows no geographical boundaries, has not been able to gain a foothold in Tunisia so far. For many years, the country lived in the slipstream of this dangerous phenomenon – although the reaction of some institutions close to the government and the party bordered on a kind of accomplice-like carelessness.

This is why it is so important that the European Union, in its capacity as the "Club of the world's most significant democracies", insists on the observance of basic rights, the principle of a peaceful handover of power, the independence of the judiciary, and the fighting of corruption – even before it expresses its wholehearted support for the process of democratic transition in Tunisia, which is suffering from the aforementioned innate deficits.

Europe's top politicians could also use their contacts to the ruling Islamist Ennahda movement to persuade them to change from a religious party to a peaceable, secular party that genuinely and without pretence supports democratic values.

The European institutions should also react fully and frankly to the human rights violations in Tunisia, which, after all, enjoys a privileged partnership with the European Union.

For example, the young Tunisian Jaber al-Majri, whom Amnesty International views as a political prisoner, has been given a harsh prison sentence of seven-and-a-half years simply for publishing photos that the Tunisian judges considered to be a "violation of Islam and morals". So far, hardly a single senior European politician has raised a finger to get him released from prison!

On the other hand, we are well aware that Tunisian-European relations are overshadowed by problematic issues such as illegal immigration and terrorism, which are also a worry for every Tunisian. Moving towards a more balanced relationship between both sides would be the most promising way of really getting a fundamental grip on these difficulties.

Tunisia, which is currently experiencing such serious economic and social turbulence, cannot overcome these problems on its own. It needs additional help and support if it is to tread this path successfully.

Soufiane Chourabi

© Qantara.de 2013

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de

Sofiane Chourabi (31) is a Tunisian writer and journalist. He is chairman of the association "Political Awareness" for civic education and was the winner of the international Omar Ourtilane Award for Press Freedom in 2011.